BSM Architecture

Commissioned to design a “small gem of a museum” Architect Raymond Moriyama, of Moriyama and Teshima Architects, achieved exactly that.

It took more than 15 years to find the right site for the Bata shoe collection’s permanent home. In the end, it was decided that the busy corner of St. George and Bloor streets, conveniently located near the St. George subway and within easy walking distance of the Royal Ontario Museum, the Gardiner Museum of Ceramic Arts and the University of Toronto, was the right choice. Proximity to these other major sites was an important consideration as the museum is intended to serve serious researchers as well as the general public.

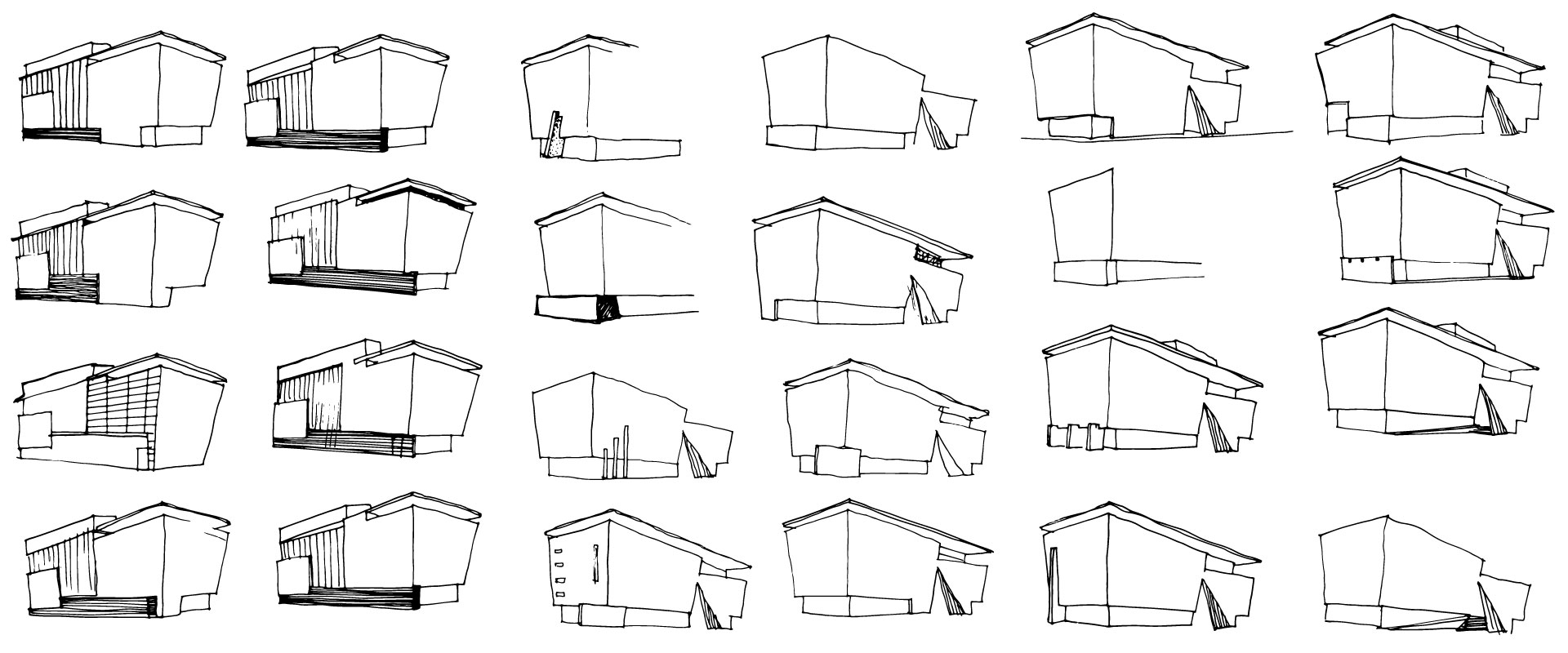

Mr. Moriyama’s considerations for how to create a building that would fully express the unbridled excitement he experienced after first seeing the collection, and how to inspire that same feeling within others, was not a simple endeavour. There were many aspects, including: function, site restrictions, budget, timeline, and concept that would impact his thinking. One thing was certain, Mr. Moriyama wanted to explore a kind of architecture that would move beyond the latest fashion.

“The intriguing idea of the museum as a kind of container took shape early on”, says Mr. Moriyama. “When I first viewed the collection I was impressed by the array of shoe boxes that protected the shoes from light, moisture and dust and played an important role in the collection.”

Moriyama’s vision had to accommodate the site’s existing zoning by-laws, building regulations and its restricted size. The initial strategy was to adopt the maximum allowable height (13.4 metres) as the major horizontal discipline plane and roof line. North along Bloor and east along St. George the edges of this plane extend from property line to property line. Similarly, to the south its edges coincide with the rear setback line. To the west it comes within inches of the neighboring building.

Guided by these parameters, Mr. Moriyama was able to maximize the buildable volume. In one of the building’s most impressive outward images, the roof plane suggests a lid resting on an open box, protecting its contents within, a metaphor that’s most obvious when viewed from the street below. The “lid’s” copper-clad soffit and fascia align with the green parapet of the building’s neighbour. As the copper oxidizes over time, the lid effect will become more pronounced and the visual link reinforced.

The building’s north and east walls, which frame the exhibition areas, are canted inward at street level by 83.5°. The effect of this is two-fold: it creates a feeling of spaciousness and provides a place for street performers, artists, musicians and other street activities. The walls are clad in a unique limestone that’s denser than granite and has a warm tone, soft sheen and fine texture that’s similar to raw leather – the basic material of the shoe industry.

The hand-picked stone from Lyons, France is sympathetic to the buff-coloured Medical Arts Building across the street (to the north) and responsive to the changing light conditions. On sunny days the reflection from the windows of the neighbouring building animates the stone walls and copper “lid” while the late-afternoon sunlight streams down Bloor Street, transforming the stone from a warm golden glow to a mauve-magenta range.

In addition to the inviting displays of natural and artificial light that continuously sweep the limestone, the building’s main entrance on Bloor Street is both alluring and intriguing. A transparent glass wedge, it virtually explodes through the building’s limestone walls and bursts onto the sidewalk. It allows passers-by an enticing glimpse right through the building, from the lobby and gift shop to the central circulation space with its cantilevered staircase of steel and glass and huge window of fractured glass set into the south wall.

Inside the five-storey building, the required elements – public facilities and exhibition, conservation and research areas – are organized in a simple, straightforward manner. The circulation core, which is dominated by a 42-foot-high window designed by Lutz Haufschild, is centrally located. East of it lie the exhibition galleries. To the west are the gift shop, multi-purpose rooms, special exhibition area and administrative offices. Two below-grade levels provide space for shoe research and storage.

The three exhibition galleries were designed as neutral spaces in order for the museum staff and exhibition designers to freely express their ideas and concepts. The task here was to provide maximum flexibility in addition to strict environmental controls and an absence of natural light, all made necessary by the age and delicacy of the objects on exhibit.

Mr. Moriyama’s fascination with the museum’s subject is clearly reflected in his frequent references to the shoemaker’s craft. Leather is used for signage and wayfinding and for the reception desk. The oversized windows in the central core display images of workshops and tools. Dora de Pédery Hunt created cast bronze medallions depicting shoes from the collection which appear on the handrails and balustrades of the central staircase.

“In summary”, says Mr. Moriyama, “architecture is never the creation of the architect alone. This building could not have been realized without Mrs. Bata’s continuous care and understanding and in developing both the concept and the numerous details. Her vision of the museum, her love of architecture, her drive, energy and insights were all instrumental in its shaping. The museum’s architecture should be seen as a celebration not only of shoes but also of the wonderful vision that has brought them into the public eye.”

For more information on the architecture of The Bata Shoe Museum, visit the Moriyama and Teshima Architect website at www.mtarch.com

Built: May 6, 1995

Location: 327 Bloor Street West

Size: 39,450 SF

Team: Raymond Moriyama, Diarmuid Nash, Jason Moriyama, and Norman Jennings

Awards: City of Toronto Urban Design Award of Excellence

Learn more about Raymond Moriyama with TVO’s documentary, Magical Imperfection: The Life And Architecture Of Moriyama.